I’ve recently* come across some VHS tapes I wanted to digitize. I’ve captured video before, both analog and digital, but I quickly found out that tapes are a completely different ballgame. I ended up diving into a deep rabbit hole of old posts and esoteric knowledge trying to put together a solution that worked reliably.

*Recently when I started writing this piece, but it’s been so delayed that it was approximately a year ago now. This post has been delayed several times, and honestly it’s a bit of a mess because of it. Sorry about that.

Why tapes are a special case

Analogue video tape is a bit crap.

I’m not talking about the image quality, although by today’s standards VHS is pretty dire, approximately 333×480 in digital terms, interlaced, and with 30-40 lines of horizontal chroma resolution. No, I’m talking about the signal quality itself.

I’m no expert in analogue video, so the technical explanation here is going to be inexact and possibly inaccurate. With that disclaimer out of the way…

Analogue video tape is a very dirty signal. Something like the composite output of a DVD player provides a clean, steady signal. Retro game consoles are a little more difficult, but generally have a steady, consistent output, even if it’s off-spec. The signal from a VCR, on the other hand, is noisy, can vary in speed, and occasionally drops out. Depending on your capture hardware, this can result in anything from weird jittery video and colour banding to intermittent dropouts to the entire capture falling out of sync or failing to get anything at all.

Add to that Macrovision copy protection, which works by deliberately making the signal even worse in such a way that’s meant to specifically confuse recording circuitry. Arguably, making digitization harder is a feature, not a bug, but it can also cause problems with modern display devices and converters.

The Current State of the Art

I’ve found it difficult to find useful information on capturing VHS tapes. Most of the information either comes down on the side of “cheapest solution possible, quality be damned” or “best possible quality given unbounded time and money”. It also seems to be one of those spaces where one or two confident voices (some of dubious authority) are blindly repeated and amplified ad infinitum.

What I’m looking for is a solution with a “good enough” result to my very subjective eye that works reliably enough that I don’t have to fiddle with it. For reasons I’ll get into in a moment, I’ve focused mostly on solutions that involve converting to HDMI and capturing that output, though I’ve also tried a few methods of direct composite capture.

I’m not going to get into the RF capture world of Domesday Duplicator and VHS-Decode. It’s really, really cool tech, and I think it fills a really important role. Museums, libraries, and universities preserving media should definitely be looking into this method. But I’m not sure it makes sense for any hobbyist, let alone a casual one like myself.

Why convert to HDMI (or: baseless speculation on time base correctors)

A device that comes up a lot in VHS capture circles is the time base corrector. Most of the information comes from a handful people, sometimes through a game of telephone, and often using non-standard and confusing terminology. In short, they clean up that dirty signal, making your captures better (or possible at all), but it’s really hard to nail down what exactly these devices do and which ones do and don’t qualify.

My understanding of them- which may or may not be correct- is something like this:

Line TBC is a feature of high-end VCRs (as well as some DVD recorders, standalone units, and maybe camcorders) that corrects for jitter on a per-line basis. I’m not exactly sure whether this is delaying or stretching, or whether it’s an analog process or digital one, but the end result is eliminating or at least reducing horizontal misalignment between lines of video. It may help compatibility with some capture cards, but this capability might be exaggerated.

Sometimes this is combined with a dropout compensator, which repeats missing lines using either an analog or digital method. This seems to be more common on its own, and I’m not sure if the features are closely related technically, or are just bundled together in feature lists. I could have sworn I’ve seen devices with similar functionality within a line (ie paste over black spots) but I can’t find any reference to that (it’s possible I just don’t know the name).

A frame TBC is more specialized, generally standalone device that retimes video frames to a consistent rate. It may retime it to an internal clock, repeating or dropping frames as needed, or may just repeat frames one for one with variable delay to “even out” the signal on a best effort basis, or it might depend on the model. I’m not totally sure if it operates on frames or fields, if it varies by device, or if it matters. The end result is that video coming in with an unstable frame rate comes out with a stable frame rate, which avoids audio sync, dropouts from lost sync and frame drop problems with capture devices.

So, that’s what a TBC is. Probably. Maybe.

The thing is, I’m pretty sure every device that converts analog video to stable digital video is at least theoretically capable of doing the same thing. This extends to some surprisingly low-cost devices. I have a generic SCART-to-HDMI scaler that can take the out-of-spec output of a Neo Geo and put out either a 50hz or 60hz signal (we’ll come back to this particular unit later). To do this, it must buffer frames and synchronize its output to an internal clock source.

To be clear, said device is crap for gaming for exactly the same reasons, and I have a RetroTINK 2X-SCART for that.

That sounds a lot like a frame synchronizer. Or gen lock. Or frame TBC. Did I mention there’s no agreed-upon terminology? Theoretically, such a device could also act as a line TBC, though I honestly have no idea if any of them do or how one would test that theory.

At the very least, a converter that can tolerate Macrovision will by definition defeat it. Theoretically, it would be possible to enforce HDCP if Macrovision signals are detected, but I’ve never seen a device actually do that and it’s probably not compliant with at least one of the specifications involved.

Provided you have a workable composite to HDMI converter, this approach has its ups and downs. The big upside is that it neatly sidesteps some major issues that render captures completely unusable- audio falling out of sync or the capture device failing to sync at all- no matter how picky your capture device is. The downside is that you’re adding something to the chain that’s doing its own processing (probably in a way that’s sub-optimal and better to do in software), and it’s not possible to get precisely every line and every frame.

My Current Solution

The solution I’ve settled on, at least for the time being, is the SCART-to-HDMI scaler connected to a Avermedia Live Gamer 2 Plus. The scaler is a generic unit that supports both composite and RGB over SCART, and though similar units are still available there’s no guarantee the actual hardware will be the same.

The quality is acceptable, especially with a bit of postprocessing trickery (which I will get to near the end). I won’t pretend it’s amazing, although I don’t feel I’m losing too much perceptually, especially if the original tape is degraded or poorly mastered. The biggest advantage of this setup is its rock-solid reliability. I’ve never had an unusable capture. I have had some with marginal audio, but I’m pretty sure that’s an issue with tracking on hi-fi stereo tapes. In those cases, capturing again with the linear audio track gets me something objectively lower quality, but with none of the issues.

While the composite-to-HDMI conversion sidesteps sync issues, it also means having basically no control over deinterlacing, overscan, sharpening, etc. It puts out a flat 60hz, even with a 59.94hz signal, it puts out a 1080p signal which isn’t an even multiple of 480 so any notion of pixel perfection is gone, and the position of the image sometimes drifts over time. In general, it does a surprisingly good job given its price, but there’s definitely room for improvement. I suspect a RetroTINK 5X-Pro in triple buffer mode would absolutely crush it, but that device is out of my price range. Maybe someday.

The Avermedia Live Gamer 2 Plus is also not the best HDMI capture device. I like it because it can be used standalone, recording to a microSD card, but its maximum bitrate is pretty low, only about 20mbps AVC. It also breaks up long recordings into several files, which is annoying to deal with and does result in a very slight stutter at the break.

Other Attempts

I did try a random Startech composite-to-USB dongle a friend gave me years ago, and as he cautioned me at the time, its output was absolute garbage. The biggest issue was that it seemed to be doing some kind of awful weave deinterlacing and if there was a way to turn it off, I couldn’t find it.

I tried a few different composite-to-HDMI devices with the HDMI capture setup before settling on the generic SCART converter. I already had a cheap unit with the (weirdly unusual) feature of a 4:3 output mode, but it was dead. I tried two new ones from Amazon: one composite only, and one slightly nicer one with s-video. Neither of those really worked at all; I managed to get a few captures with weird colour banding, and total garbage the rest of the time.

I spent way too much on an Extron IN 1604 HD hoping it would perform better than the generic units. One of my friends uses a similar device with good results, but I didn’t have the same luck. While the output looked better when it worked, it didn’t look that much better, and it would regularly drop out and display a black screen for several seconds, which made it basically unusable in practice.

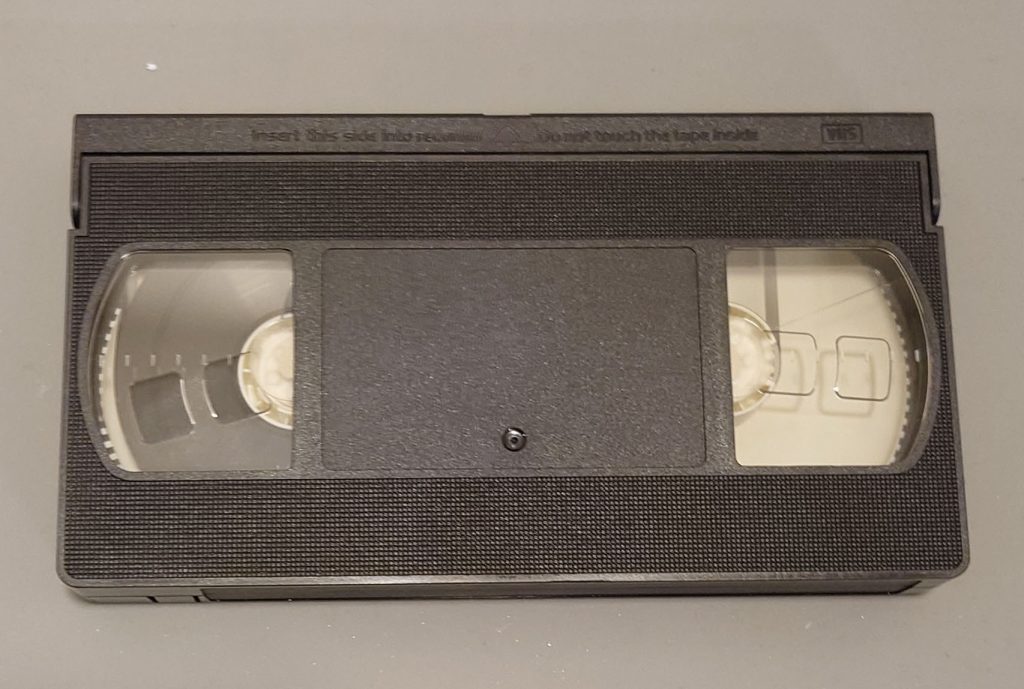

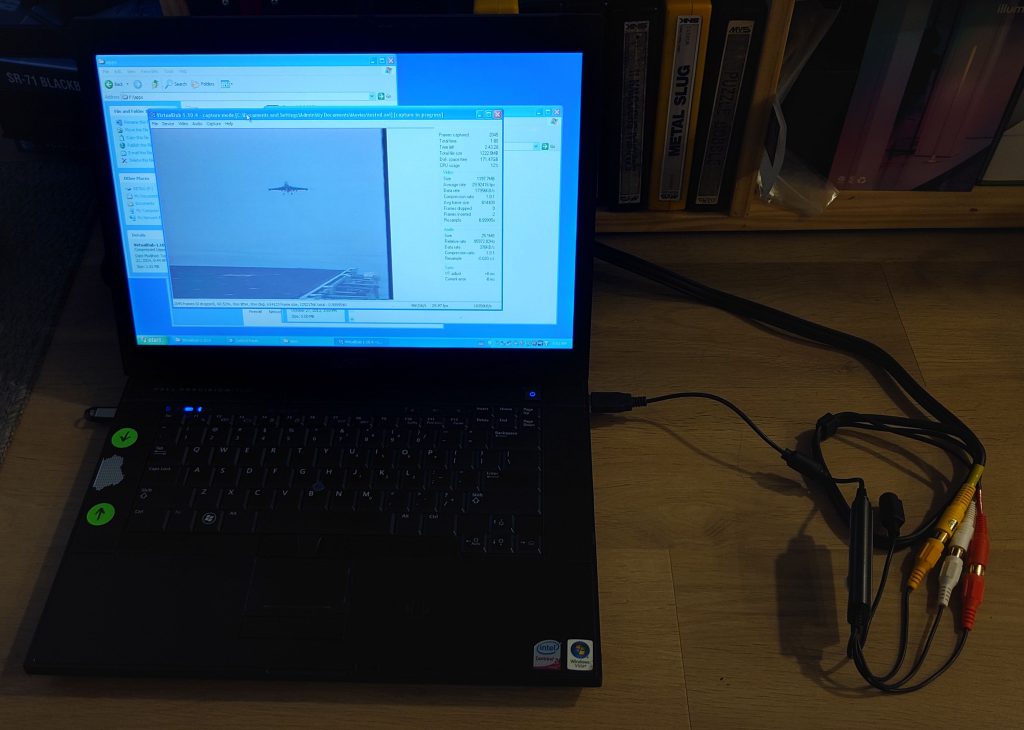

One interesting solution that I have seen promulgated is using an old camcorder with analogue inputs as a bridge, and I just happen to have a nice Sony Digital8 unit. I’ve tried this, and it produces better results than my usual method… when it works. I’ve been unable to work out the kinks to the point where it works reliably. After trying many, many different combinations of hardware and software, I was finally able to repeatably capture entire tapes without the capture locking up or dropping out (Dell Precision M4400, Windows XP, VirtualDub, by the way), but I’m still getting audio issues half the time. I might come back to it some day, but I’ve kind of reached a point where I feel I’ve wasted enough time on it and I don’t want to keep poking at it.

It does work pretty well in reverse for making tapes, though, and that’s something I might cover in another post in the future.

Postprocessing and Philosophy

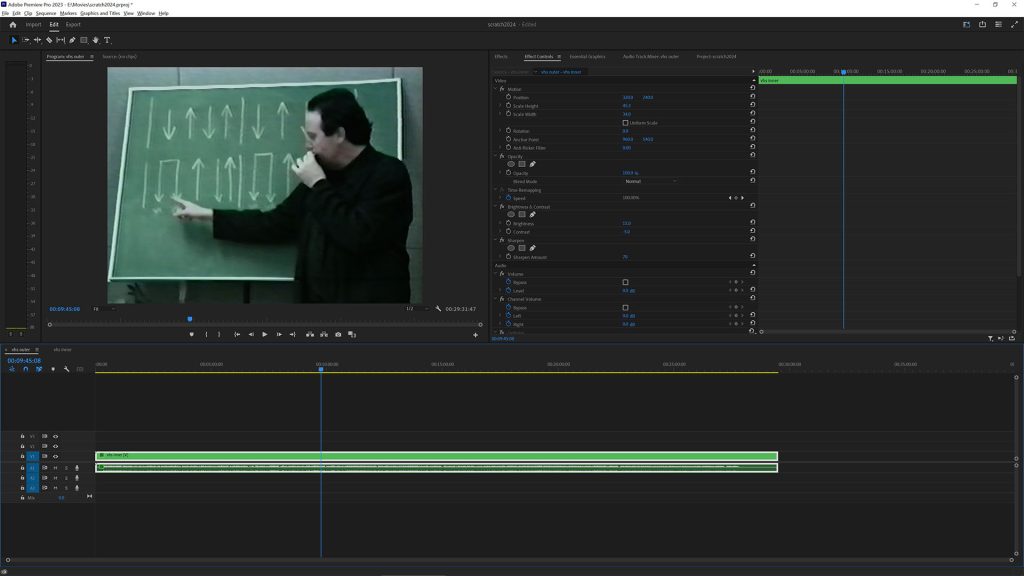

I’ve experimented with a few different ways of postprocessing the videos, but I eventually settled on a consistent process. I do all this in Premiere Pro- I’d experimented with trying to do it in ffmpeg before, but it’s just too awkward to be worth it.

- Combine all the segments into one sequence (let’s call it the “inner” sequence). This sequence is 1080p, like the source footage

- Trim the junk off the start and the end

- Drop that inner sequence into another sequence (let’s call it the “outer” sequence). This sequence is 640×480, which is what the output will be

- Scale the inner sequence down to fit. Usually I crop a little bit, too.

- Add 6db of audio gain. I still have no idea why this is necessary.

- Add a brightness/contrast effect, to taste. Usually I do -5 to -10 contrast, +15 to +25 brightness

- Sometimes add a sharpening effect with between 50-100 strength

- Sometimes add an audio noise reduction effect with the “light” preset

- Export as a 1mbps HEVC/128kbps AAC mp4 file

I’m sure the purists are screaming right now. While it’s true that the final result is far from a lossless HuffYUV capture, VHS tapes are pretty limited to begin with and the result is still plenty watchable.

And now, we come to my core philosophy when it comes to archiving, which will surely ruffle some feathers:

The bad copy you have is infinitely better than the good copy you don’t.

I’m not going to call out any names, but I’m going to offer rebuttals to specific points I’ve heard time and time again.

Let’s address the “non-archival” low-bitrate HEVC encode first. A lossless true-archival copy is thirty times larger, perceptually similar, and can’t easily be watched on other devices. If wishes were fishes, that’s still how I’d store them, but the reality is that I don’t have an unlimited amount of hard drive space. To me it’s a better tradeoff to store 30 videos in acceptable quality than 1 in great quality, and 29 not at all.

On top of that, properly backing up huge video files can be prohibitively expensive. Offsite backup in particular doesn’t have a lot of cheap options, especially if you don’t have a place to colocate your own hardware. Coming back to the core philosophy, better to have three copies spread around in a redundant way rather than a single one a drive failure away from being none, even if those three copies are worse.

Similarly, I think it’s far better if 50 people digitize a tape using imperfect method than one person getting a perfect RF capture, especially if that one person doesn’t distribute their copy. Again, it’s too easy for that one copy to become no copies.

Why not wait? Don’t half-ass it now, but wait until you have a better capture setup and the time to do it right. The problem is that day may never come. I don’t think I’ll ever have thousands of dollars to spend on the esoteric hardware needed (some of which gets rarer and more expensive each year), nor be in a place where I have time to set it all up and monitor every tape as it gets captured. On top of that, storing tapes has its own issues- they degrade over time, and a fire or flood could wipe out the physical collection. Finally, while some people have space to keep boxes of tapes around, not everyone does, and I’m firmly in the latter category.

I’m valuing ease of use and reliability very highly, even over quality. This is, in the end, a minor hobby for me that I don’t have a ton of time to dedicate to. Above all I don’t have time to babysit tapes as they capture. If I have a tape with hi-fi audio issues, I’ll just capture it again with the linear audio track. Maybe I could tweak the tracking to get the hi-fi track to work, but I just don’t have time for that.

Why bother at all, then? I think there’s some magic to a swarm of amateur archivists, all with their own distributed copies, digitizing the weird and wacky stuff they find, that otherwise might have been missed. That is not to say the pros and serious hobbyists with elaborate setups making true archival copies don’t have their place. In the end, I think we need both, but I think it’s foolhardy to push people who are firmly in the former category toward trying to be the latter.

There is one thing I’m on the fence about, which is the zoom and crop and output at 640×480. I figure it’s not a big deal because we’ve lost all semblance of being pixel- or line-perfect long before this step, but it might be better to work and output at a higher resolution (supersampling).

In Conclusion

Although I do feel my current setup is good enough, I’d like to get a few notches up the quality ladder, and there are a few tapes I’m saving in the hopes I’ll be able to get there. If I could only upgrade one, I’d prioritize upgrading the scaler, but I might look into a better HDMI capture device as well at some point.

Between when I started writing this piece and when I finished it, RetroRGB put out a video on using a RetroTINK-5X (or 4K) for capturing VHS tapes. Though it’s not perfect, it’s extremely promising, and just about hits the right balance of quality, ease of use, and cost I’m looking for (the RetroTINK-5X is just a bit too spendy for me right now, but maybe someday).

If there’s one key takeaway here, it’s the importance of finding a solution that works for you, achieving a result that you consider good enough with the time and money you’re able to invest. That goes for a lot of things, not just video capture, but I think it’s a really good example given the breadth of devices available and how often recommendations are rashly repeated without regard to the context.